By Richard Westlund / Special to UM News

UM scientists and physicians are attacking the Zika virus on numerous research fronts.

Under the Zika Research Grant Initiative, the Florida Department of Health in February 2017 awarded the University of Miami $13.1 million to fund 12 Zika research projects.

Now, UM labs are bustling with teams of scientists working to detect the virus in its active, infectious stage or if there has been a prior exposure, as well as developing a vaccine, preventive treatment or anti-viral medications that can be given safely to pregnant women.

“We have learned a great deal about Zika since it emerged as a serious health threat to South Florida last year,” said Sylvia Daunert, professor of biochemistry and molecular biology and the Lucille P. Markey chair of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine. “This is a team effort.”

Sylvia Daunert, professor of biochemistry and molecular biology and the Lucille P. Markey chair of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine

Long before Zika emerged as a threat to South Florida, UM scientists were collaborating with tropical disease research institutions and scientists in Latin America. For the past 12 years, renowned immunologist David Watkins, professor and vice chair for research, Department of Pathology at the Miller School, has been working with researchers in Brazil like Esper G. Kallas, M.D., a prominent infectious disease specialist at the University of São Paulo.

David Watkins, professor and vice chair for research, Department of Pathology at the Miller School of Medicine

Thanks to that relationship, Watkins has been able to obtain samples from Zika-positive patients in Brazil, jump-starting his own laboratory research. In the past year, he developed a test that can detect the antibodies produced by the immune system in response to a Zika infection.

“We are applying for emergency use authorization from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the Z-Quick test, which gives results in two or three days,” he said. “We hope it will soon be available here for women who are planning a pregnancy.”

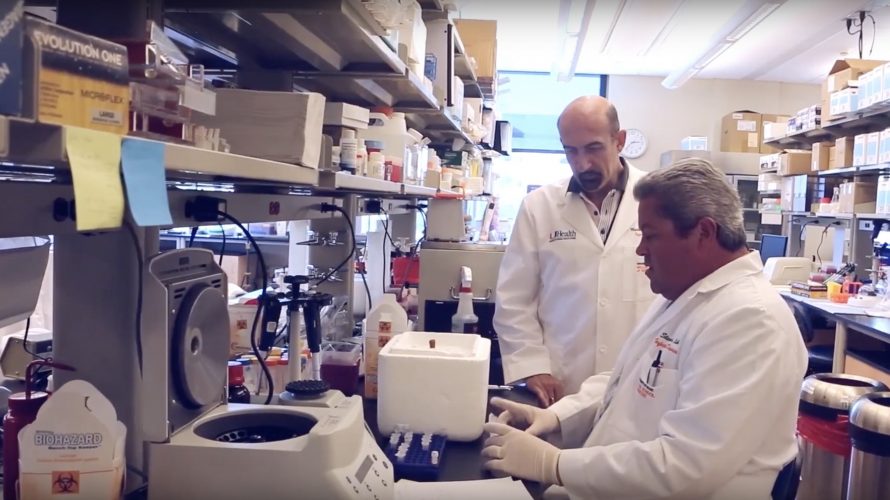

In another UM laboratory, Mario Stevenson is focusing on developing a diagnostic test using body fluids, rather than blood.

“We are trying to understand how long the virus stays in the body,” said Stevenson, professor of medicine, chief of the Division of Infectious Diseases and director of the Institute of AIDS and Emerging Infectious Diseases.

Mario Stevenson, professor of medicine, chief of the Division of Infectious Diseases and director of the Institute of AIDS and Emerging Infectious Diseases

“Even though it may be cleared from the blood plasma, it could still be present in red blood cells, semen, urine or saliva. If there is such a reservoir for the virus, there is still a risk of transmitting Zika to your partner and unborn child.”

Daunert is also moving closer to new Zika diagnostic and treatment strategies, including point-of-care-testing to provide a rapid result without the need for sophisticated instrumentation.

“A pregnant woman bitten by a mosquito experiences a great deal of anguish about Zika, and being able to tell her ‘yes’ or ‘no’ on the spot would be of tremendous help,” she said.

In collaboration with Watkins and Sapna Deo, associate professor of biochemistry and molecular biology, and using the antibodies from the Watkins lab, the team has developed a test where a drop of blood or urine is placed on a paper strip, and the results appear in less than an hour.

Daunert and Deo are also working on a test to detect the nucleic acid (DNA) of the Zika virus to determine if a pregnant woman has an active infection.

Sapna Deo, associate professor of biochemistry and molecular biology at the UM Miller School of Medicine

“Our test is very specific for Zika because it has been isolated from infected patients in Brazil,” Daunert said. “That’s important because other mosquito-borne viruses can also trigger antibodies, and patients need to know the nature of the infection.”

In addition, Daunert, Deo, Shanta Dhar, associate professor of biochemistry and molecular biology, and Dushyantha Jayaweera, M.D., executive dean for research and graduate and postgraduate education, are studying how advanced nanotechnology might be used to treat Zika infections.

“Drugs used to fight the virus have a toxic effect on the body, and may not be safe to use when treating pregnant women,” Daunert said. “Our laboratory is working on converting those toxic drugs into nanoparticles than can be readily absorbed by the body in much smaller doses. If the initial laboratory studies look promising, this approach could be used as a preventive tool, like getting a shot for malaria or yellow fever before traveling to the tropics.”

If the nano-formulation is successful, Daunert plans to extend the research into potential treatments of other viruses.

“Our goal is to develop a ‘plug and play’ platform to deal with Zika today and perhaps chikungunya, yellow fever or another new virus tomorrow,” she said. “These are all serious threats to human health and we need to be prepared for the future.”

Share this Post